(This piece was originally published in June 2020 but was edited and updated in December 2020 for my charity compilation Fresh Hockey Takes 2020. The article below is the updated text.)

In the past three seasons, Columbus Blue Jackets defenceman Seth Jones has become almost universally recognized as one of hockey’s truly elite blueliners. A noteworthy performance in the 2020 playoffs in which he broke the NHL record for minutes played in a game only heightened his reputation, and it’s not difficult to understand why. He has the hallmarks of an elite defenceman: he puts up points at a reasonable rate (on pace for between 40 and 57 the past five seasons), he’s big but can skate, he plays huge minutes, and he stands out whenever you watch Columbus play. When he’s up for free agency in two years, he’ll probably receive over $9M dollars annually, either from the Jackets or somebody else. Two weeks in the spotlight have established him almost unanimously as a top-five defenceman, and you very frequently hear him described as the best in the world.

There’s one small dissenting voice amid this coronation though: the analytics community. Those buzzkills. While Jones isn’t one of that small coterie of players with an elite rep and abysmal underlying numbers (we’ll get to Drew Doughty later), his on-ice results have been mostly unremarkable since joining the Blue Jackets. This tends to be quite surprising to most hockey fans because the last word that would come to mind from watching him play would be “unremarkable.” This might be the biggest chasm between what the stats say and what the eye test suggests in hockey at the moment, and I'm going to do my best to bridge it. First, I’m going to provide an overview of Jones’ analytical profile, including his individual impact on a variety of offensive and defensive stats, his time on ice and usage, and his microstats. Then, using the eye test, I’m going to determine what it is that Jones does that looks elite but doesn’t necessarily translate to elite outcomes. I think this divide is actually pretty explainable, and gets to the core of why macro-level analytics are such a valuable tool of player evaluation.

His On-Ice Results Are Average at Best

First thing’s first: Seth Jones is a very productive player. Among defencemen since the 2016-17 season, Jones has ranked 16th in points, 9th in even strength points, 19th in even strength points per 60 minutes, 18th in even strength goals per 60 minutes, etc. I don’t particularly value points as a primary way to evaluate defencemen (especially since they tend to suddenly drop when a player like, say, Artemi Panarin leaves a team), but I would be remiss without mentioning this.

To get a decent idea of how Seth Jones impacts his team (especially defensively), we can’t just use raw stats. That’s true of analyzing any player, but it’s particularly important here considering that in the past five seasons Columbus’ team defence as measured by 5v5 expected goals against has improved from 23rd in the league to 3rd. We need to use stats that account for all the contextual factors that could screw with the results - that includes quality of competition, quality of teammates, zone starts, game situation, etc. We also have to remember what it is that these types of analytics value. The stats here are what I would call “macro-stats'' - they’re built from models that use ridge regression to determine a player’s isolated impact on offence and defence. On offence, a defenceman’s job is to contribute to his team getting strong scoring chances. On defence, their fundamental task is to prevent their goalie from facing high-quality chances against. Any of the actual things they do on the ice - blocking shots, making breakout passes, sending pucks up the boards, etc. - are components serving those two core goals. So if a player is the best in the league at blocking shots but also allows a disproportionate number of shots from the slot, he’s not elite defensively - what exactly is the point of all those blocks then?

So let’s take a look at how Jones ranks in terms of his impact on expected goals for and against compared to other blueliners in the NHL in the past three seasons using Patrick Bacon’s beta Wins Above Replacement model. The even strength offence and defence outputs of this are based directly on a player’s cumulative impact at driving scoring chances for and against. Based on his reputation and the number of minutes he plays, you would expect to see Jones’ defensive numbers near the top of the league with his offensive numbers not far behind. But that’s not the case:

Since being acquired by the Blue Jackets, Seth Jones has turned into a responsible defensive player, largely at the expense of his offensive contributions. But he hasn’t been elite defensively by this measure at even strength either, peaking at around the 74th percentile in 2018-19.

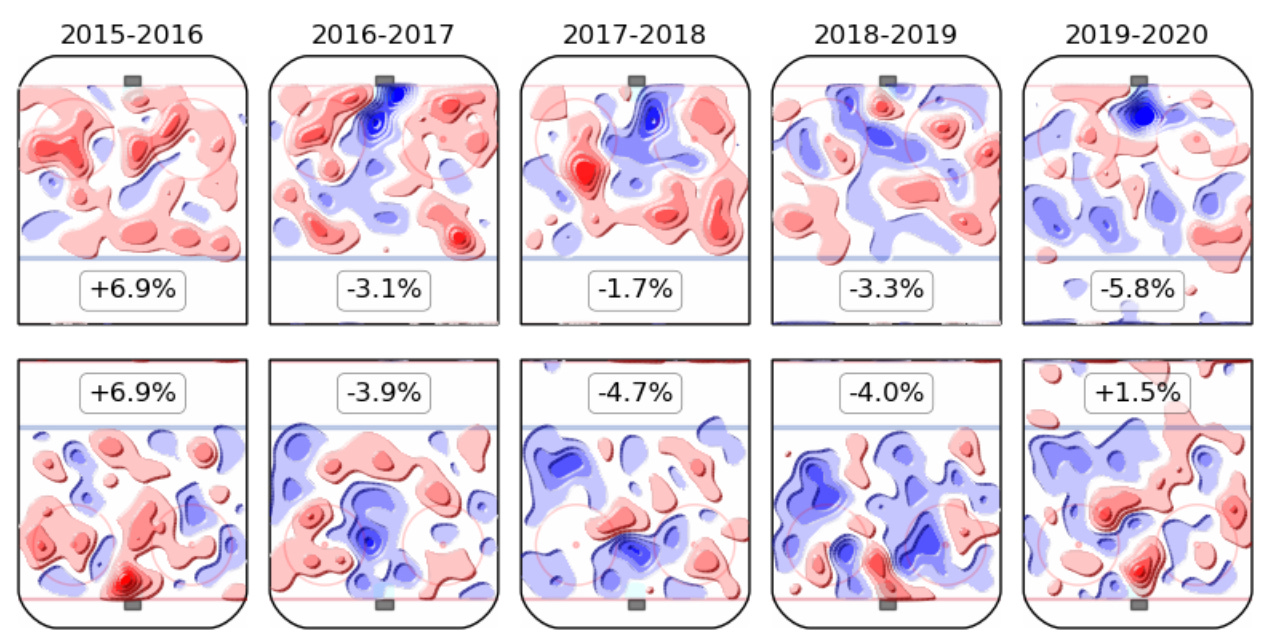

Jones is supposed to be among the top two-way defencemen in the league, and yet he’s never been exceptional at both ends of the ice simultaneously. This aligns with the findings of Micah Blake McCurdy’s isolate model as well, which uses rates instead and never assesses him as better than low-event at even strength at any time in his career:

Additionally, while it seems unfathomable to say that the Jackets are just as good without Jones on the ice, the numbers bear it out. In the past three seasons, Columbus has had exactly the same percentage of goals for at 5v5 (52.82%) with Jones off the ice as on the ice, and only a slightly smaller xGF%. The same is even true of some of his teammates. Ryan Murray has been significantly better apart from Jones by expected goals for percentage and expected goals against, as has Markus Nutivaara. The only regular Jackets defenceman whose results benefit from playing with Jones is Zach Werenski, but to be fair to him Jones is also much better with him than without him - they make each other better. With Or Without You stats are flawed, as they leave out valuable contextual information, but as Jones’ ability to elevate his linemates is often cited as a strength of his I thought it was worth mentioning.

And since I know it’s going to come up, no, losing Seth Jones to injury is not why the Blue Jackets collapsed in February. As I’ve pointed out elsewhere, the post-Jones-injury Jackets were still the 8th best defensive team in the league in terms of quality chances against; what really happened is that the Jackets goaltending went from 1st in the NHL to 28th in that time. So unless we should be talking about Seth Jones as a contender for the Vezina Trophy, evidence suggests that it just turned out that Elvis Merzlikins wasn’t the best goalie in the NHL and he regressed rapidly to the mean - as one might expect him to.

Seth Jones’ individual impact on his team’s ability to generate offensive chances and prevent scoring chances against has been average at best during his time in Columbus. But what about his deployment?

Big Minutes + Top Competition = Elite?

That TOI/GP is so often used as a reason why a defenceman is elite is reflective of the lack of mainstream stats that measure defensive play in my mind. Yes, most elite defencemen play big minutes, just like most elite forwards do. It makes sense that they would; if your team has an elite defenceman, you should play them a lot. But playing big minutes against tough competition isn’t a skill in and of itself - it’s a coaching decision. Where the elite skill comes in is excelling in those circumstances, and statistically speaking Jones hasn’t done that. You should be skeptical when someone tells you that a player is good just because they play big minutes, because what actually matters is how they play in those minutes.

But let’s actually dig into Jones’ usage a bit. Seth Jones played the 7th most minutes per game among defencemen this season. But it might surprise you to learn that according to PuckIQ, Jones actually wasn’t deployed against top competition that much, ranking 66th in that category. In terms of time against top competition as a percentage of ice time, Jones ranked 139th out of 233, 5th among Jackets defencemen. Tortorella appears to deploy his top two defensive pairs fairly evenly from a matchup perspective, trusting Savard and Murray almost as much.

But this also provides a good opportunity to interrogate what playing against top competition actually means, and the value of that concept in general. Intuitively, it might seem as though a player’s competition matters a lot - playing against Sidney Crosby is a lot different than playing against Justin Abdelkader. But what most people don’t realize is that match-ups are far less set in stone than you might think. Players play against everybody, and while some might see top lines slightly more than others, the variance is not very dramatic at all. Patrick has quantified that with his Time On Ice Percentage Quality of Competition/Teammates metric, which determines the average competition and teammate of a player using time on ice %. He found that the difference between the player who faced the toughest competition (Brayden McNabb) and the easiest (Robert Bortuzzo) is 29.8% vs. 27.5%, which is extremely small. In contrast, the difference between the player who played with the best teammates (Zack Kassian) and the worst (Logan Shaw) is 33% vs 24.6%. That’s because while coaches might sometimes try to control matchups, everyone’s still going to play against everybody. What’s far more stable and controllable is who you play with. Playing mostly with guys like Werenski and Bjorkstrand and Dubois matters a lot more to Jones than facing top lines slightly more than some other defencemen do. When you hear someone talk about a player being good because they “play against tough opponents”, the first thing you should ask is “okay, but who do they play with?”

So if a key component of the reason you think Jones is top-5 in the league is his tough deployment in terms of minutes and competition, you should keep all of this in mind. You should also ask yourself why you don’t consider Thomas Chabot to be elite as well?

Chabot played even bigger and tougher minutes on a much worse team and had better results across the board than Jones, whether you’re looking at raw numbers or relative ones. It’s worth keeping in mind.

So this season at least, while Jones certainly plays a ton of minutes, he doesn’t play as much against top competition as you might think. But have you seen his microstats?

Microstats

When I first stuck my neck out by pointing out Jones’ meh underlying numbers a few months ago, I was told by multiple people that while his macro-level shot and chance impact stats weren’t amazing, I should consider that he’s an elite transition player. While I think microstats like this are an invaluable tool for evaluating the way a player plays, determining what their skills are, and discovering what makes them effective or ineffective, I don’t think that a player who excels in specific areas of the game but has underwhelming overall results should be considered elite. Nonetheless, I would not be doing my due diligence if I didn’t look into this at least.

Most microstats are unavailable to the general public because they have to be tracked manually, which takes a lot of time and effort (and venture capital). Fortunately we have the heroic efforts of Corey Sznajder, who does the analytics community an immense service by watching hundreds of games and tracking minute details of them for public consumption. Looking at Seth Jones’ numbers from the past three combined seasons visualized by CJ Turtoro, you can see where his reputation for excellent transition play comes from:

Jones ranked near the top of defencemen in entering the offensive zone with possession of the puck and very well on the breakout as well. He was extremely active and efficient in the Blue Jackets’ transition game. It’s clear that Seth Jones controls the puck a lot, affirmed by the comments made by the Jackets’ coaching staff in this article by Alison Lukan discussing some internal metrics tracked by the organization (which include puck touches and breakouts). Something worth noting, however, is that Jones’ transition play took a major hit this season. He was much more focused on leading the rush himself rather than facilitating it through passes, and he dumped the puck out of the defensive zone a lot more.

In fact, according to Andrew Berkshire, this has become so much of an issue that the private data actually suggests that the Jackets’ transition game got better after Jones got hurt.

As I’ve said before, I consider microstats to function as EyeTest+ - they quantify the events we see on the ice so that we can compare players to each other in certain facets of the game (and so we don’t have to watch all 1,230 games every season). That’s why I think it’s fair to say that the disconnect between the microstats and the macrostats is directly reflective of the eye-test vs. analytics thing here. When you’re watching a game, your eyes are drawn to the things defencemen do with the puck, not what they do without it. Jones’ talent on the breakout leads to eye-popping zone entries, and yet his teams consistently get fewer and lower-quality scoring chances when he’s on the ice.

Bridging the Gap Between the Macrostats and Eye Test

I’m not a brilliant hockey tactician by any means. I was intramural captain of the year once in university, but that was mostly due to the fact that we improbably didn’t forfeit any games that season because of lack of attendance. In all honesty, my eye test is probably roughly equivalent to most fans’. Nonetheless, I was curious to see what the hell was actually going on with Jones - how do the WAR, RAPM, and isolate stats contradict the eye test and microstats so much? Like most people, I had seen him play a bunch of times against my favourite team and in the playoffs and I had generally been impressed by him as far as I can remember. But in that fundamental flaw of the casual “eye test,” I wasn’t exactly isolating on him in those viewings.

So I watched him play. Jones’ talent when it comes to handling and passing the puck is extremely apparent. He’s noticeable when he’s on the ice and he’s very active in the play outside of the offensive zone - it’s no surprise that he fares very well in the Jackets’ internal “puck touches” stats. His breakout passes are generally pretty short and low-risk, which likely explains his very high success rate. But his favourite play is to carry the puck through the neutral zone and cross the offensive blueline with possession - he did that many times during the 2020 playoffs. This looks really impressive, because he’s a strong skater for a player his size and carries the puck confidently. But as Scott Wheeler and Dom Luszczyszyn pointed out in their own game tape analysis, Jones leading the rush so often isn’t necessarily a good thing. Most of the time, these plays don’t end up going anywhere once Jones actually gets into the offensive zone, and they can even result in him getting caught up the ice during the resulting counter-attack.

For as effective as Jones was at driving transition offence, he was far less of a difference-maker in the offensive zone. His playmaking ability was occasionally apparent, but far too often he took very low-percentage shots that were either blocked or easily saved. When he completed passes they were almost always to his defensive partner or a player on the perimeter. This made me think of the way that he’s almost always driven shot attempt quantity far more than quality:

Overall, Jones looked far less confident handling the puck in the offensive zone despite getting frequent touches, and often got rid of it hastily when he had time to make a better play.

Secondly, I noticed some things in the defensive end. As you might imagine, Jones was very active in his own zone, getting a lot of touches and winning puck battles using his skating and size. We all remember those instant replays in the Toronto series of him hounding Mitch Marner and Auston Matthews below the goal line. But I noticed that in doing so he almost always pushed the puck to an area where his opponents were able to recover it and continue keeping possession. Additionally, when defending against the rush Jones allows his opponents to enter the zone more than almost any defenceman in the league. He plays a very soft gap and in doing so allows the other team to establish possession and trap the Blue Jackets in the defensive end. This can be a strategic decision made by players or coaches to protect the inside, but skills coach Jack Han argues it’s the product of technical issues with his agility:

Jones’ way of masking his inferior glide, then, is to play a looser gap across the neutral zone. This allows him to take an extra backward crossover to match speed or to pivot to forward skating while still protecting the middle of the ice. But this also destroys his ability to deny the blue line.

So how does all of this add up? Han has a great framework for thinking about what is overvalued and overvalued for defencemen in all three zones that applies directly to Jones. The overvalued qualities look great to the eye test but don’t add up to results, while the inverse is true of the undervalued ones.

The Defensive Zone

Overvalued: Physical toughness and the ability to box out

Undervalued: Ability to find a continuation play instead of dumping the puck out

Jones, especially in the playoffs, excels at the former. It sure as hell catches the eye - you’ll hear the commentator say “He’s hounded by Jones” and they’ll show an instant replay of him cross-checking Matthews in the back repeatedly. But while it might limit some of what an opposing forward can do, it often won’t end possession in a meaningful way. Meanwhile, Jones’ increased issues with moving the puck out through passing rather than dumps or carries have taken a toll on his results.

The Neutral Zone

Overvalued: Solo carries from the DZ into NZ into OZ

Undervalued: Jumping past your check in the DZ and attacking the space in the middle of the ice, off the puck.

Jones does both of these things, but it’s his propensity to do the former that really grabs your attention. As I said above, I find Jones’ love of personally carrying the puck into the zone to be one of the biggest issues with his game’s efficiency because those one-and-done plays tend to be more risk than reward. Once again, the commentator goes “And here’s Jones again, carries the puck across the line, sends a pass out in front, and it’s just missed by Dubois” and your reaction isn’t “oh nothing really came of that,” it’s “wow, look at Jones leading the offence!”

The Offensive Zone

Overvalued: Taking lots of shots from the point

Undervalued: Holding the puck and running high cycle plays with F3 to create better looks in the slot area

Jones doesn’t just stand at the blue line and fire shots, although as mentioned above he does have that instinct to chuck them on net. But his cycle plays do tend to take him to places where he doesn’t generate a whole lot. The Jackets don’t generate a whole lot in the slot when he’s on the ice, and a big part of that is because instead of trying to find his teammates in the slot through high cycles he often likes to jump up all the way below the red line and try to do it all himself.

Overall, if there’s something that looks elite but doesn’t necessarily lead to real on-ice results, Jones is brilliant at it.

Isolating on Jones at even strength using the eye test helped illuminate where the differences between his statistical profile and reputation come from: excellent transition play marred by underwhelming offensive zone participation and defensive zone issues.

Conclusion

I find Seth Jones to be a really fascinating player. I agree with those who say that he’s a perfect illustration of the disconnect between analytics and the eye test, but while they might mean that it proves that analytics are fundamentally off-base, I think it shows exactly why they’re valuable. I don’t think that the gulf between how Seth Jones looks from the eye test and the analytics is irreconcilable at all; it’s as clear a representation of the way that certain attributes and skills stand out to the eye test even if they don’t lead to measurable results.

If you looked at his statistical and analytical profile (outside of just point totals) without his name attached to it, it would be absolutely impossible to impartially conclude that Seth Jones has played like a top-pairing calibre defenceman, let alone an elite one, in his career. By the best models that we currently have to isolate players from the kinds of context factors that affect their results, Jones has been a pretty unremarkable defenceman at even strength since he’s arrived in Columbus. While he’s said to be one of the most dominant defensive players in the league, at the core function of defence (preventing your goalie from having to face quality chances against) he’s been only a bit better than average.

And yet, those who regularly watch him (and those who don’t, but listen to those who regularly watch him) consider him to be a top-five defenceman in the league and an annual Norris contender. I believe that this is in large part because he is so active in the play; his ability to break the puck out consistently without turning it over and carry it into the offensive zone with so much poise is amazing to watch, and his natural physical talents are often on full display. He uses those gifts in the defensive end, breaking up plays along the boards effectively with his stick and using his body to push forwards out of dangerous areas. His activity in transition is probably a big reason why he gets so many points as well, and he has a good shot. It’s impossible not to notice Seth Jones when he’s on the ice.

But it’s the things that the eye isn’t as drawn to that explain why despite all of that he profiles analytically as such a mediocre defender. Players like Jones force us to consider the ways that flashy displays of talent do not necessarily translate to macro-level on-ice results; how a player can be really good at certain very visible things but quietly ineffective in other areas. I do not think Seth Jones is an elite defenceman, because to me an elite defenceman is one who marries their physical skills with the ability to tilt the ice in his team’s favour. An elite defensive defenceman must not only break up passes or win puck battles, but prevent his goalie from facing great chances in other less noticeable ways. An elite offensive defenceman must not only carry the puck in and score goals, but use strong judgement and patience in the offensive zone to ensure that his team consistently generates quality scoring chances. An elite two-way defenceman must be strong in both regards. Seth Jones is excellent at many things, but the evidence suggests he does not fit that description.

Shea Theodore has been much better than jones over the last 3 years