Breaking Down Shea Theodore's Offensive Impact

Do the stats tell the whole story with Vegas' analytical darling?

These playoffs have been a coming-out party for Shea Theodore. He’s tied for ninth in postseason points with 17 in 17 games, has scored some incredibly timely goals including the game-winner in Game 7 against the Canucks, and has been impressing the hockey world with his smooth skating, pinpoint passing, and ability to create offence. For some, this is a shocking breakout. For those in the analytical community, it was only a matter of time.

For the past two seasons, Shea Theodore has been essentially the definition of the “analytical darling” defenceman. Despite not putting up the kinds of point totals that typically command Norris attention, he has put up pretty stunning results in areas of the game that stats nerds value - whether it’s expected goals, Corsi, or even microstats like zone entries and exits. Whereas a few months ago including Theodore on a Norris ballot or a Team Canada Olympic roster would garner scorn (or at least some confusion), after these playoffs it’s pretty much assured that he’ll be viewed as a top-tier defenceman for the forseeable future. A pretty big vindication for the stats crowd, eh? The first part of this breakdown will look at Theodore’s underlying numbers and explain why he gained his reputation in the first place and why it’s actually unsurprising that he’s broken out to such a great extent.

The second part is a bit more complicated. In the process of looking into Theodore’s stats I noticed something very odd about his numbers that wasn’t explainable just by using the macro-level stats I usually do - something that suggests that his on-ice impact might have been far less positive than it initially seems. This led me down a rabbit-hole that tested the limits of publicly available data and forced me to rethink some prior assumptions about evaluating certain unique defencemen based purely on how well they drive scoring chances. I understand that this could be read as tedious contrarianism - call a guy elite until everyone else does, and then turn on him, eh? But I hope that it will come across more as what we all want from an analytical approach to hockey: finding a question that the models can’t fully answer, and use a combination of critical thinking, eye test analysis, and creativity to figure it out.

The Case for Shea Theodore as Elite

Analytically speaking, Theodore is a stunning player and arguably the league’s best offensive defenceman. No blueliner has a greater isolated impact on driving scoring chances, and in the past two seasons combined he leads the NHL in RAPM xG differential (combined offensive and defensive expected goal impact). He has an above-average ability to finish his own shots, which is remarkable considering how many of them he takes. He plays top pair minutes and the powerplay and thrives in both settings.

This doesn’t change when you look at microstats either. Theodore’s control of the puck all over the ice is almost unparalleled, as Vegas trusts him to lead the breakout, carry the puck into the zone, and shoot - a lot.

This extends to the data collected by private companies as well. SportLogiq ranks Theodore 1st in stretch passes, 3rd in slot shots, 3rd in one-timers, and top ten in a variety of zone-entry based stats including entries with possession and entries leading to a shot on goal. He’s mobile, active, and not afraid to join the rush or get to the slot.

So What’s the Matter, Then?

In principle, when evaluating defencemen analytically from a macro-level perspective, what really matters is their expected goal driving, not actual goals. This is because the gap between actual goals and expected goals is generally understood to be caused by factors mostly outside of a blueliner’s control - goals against above expected are the fault of goalies, while goals for above expected can be credited to the shooting talent of forwards. That Theodore ranked only 24th in 5v5 points and 54th in 5v5 points/60 this season as an offensive defenceman is beside the point as a result… or is it?

The problem with declaring Theodore one of the league’s best defencemen is that he’s an anomaly in two very consequential areas that could be confounding existing analytical models and our typical means of interpreting them.

Shea Theodore is sheltered more than any other defenceman playing even close to the number of minutes that he does.

Shea Theodore has a massive and consistently detrimental effect on Vegas’ ability to finish their scoring chances. This means that his positive impact on expected goals does not translate to actual goals.

Let’s break those down.

Shea Theodore is Sheltered More Than Any Other Top-Pairing Defenceman in the NHL

When people say a defenceman is sheltered, it means a few things - they start a high rate of their shifts in the offensive zone, few in the defensive zone, and play against relatively easy competition. Most of the time, the effect of these factors is overstated; every blueliner in the league started over half of their shifts on the fly this season anyway, and the variance between “competition” levels is relatively small. Nonetheless, the extent to which Theodore stands out in both respects is worth noting. The zone starts are less egregious (why wouldn’t you start your best offensive defenceman in the offensive zone?) but the competition aspect is striking.

On the diagram below (courtesy of HockeyViz), the right side shows Theodore’s. competition ranked by their average time on ice with the red line indicating “average deployment.” Notice the gap between the blue and red for the top three? That’s there because Vegas’ coaches play Theodore even less against other teams’ top lines than a league average defenceman usually does.

Based on the only publicly available competition model, PuckIQ’s Woodmoney, I’ve estimated Shea Theodore’s Quality of Competition to be in the 26th percentile based on the distribution of his ice time playing against top, middle, and bottom-level competition. That means almost 75% of the league’s defencemen faced harder competition than him. To put that in perspective, Theodore played the 46th-most minutes per night among defencemen this season. The next most-played blueliner with comparable sheltering is Keith Yandle, who ranks 104th.

To compensate for keeping a 22-minute-a-night defenceman away from top lines, Brayden McNabb and Nate Schmidt are given the 4th and 6th toughest deployment in the NHL respectively. It’s why Theodore’s most frequent forward opponents this season were Tyler Ennis and Brayden Schenn and Schmidt’s were Leon Draisaitl and Anze Kopitar.

All the macro-level models out there, including the ones I’ve cited above, adjust for quality of competition. But Theodore’s deployment is the type of extreme anomaly that models - rightfully - aren’t built with in mind. As someone experienced in the analytics community told me, “hockey populations are rarely normally distributed but we pretend they are for most modeling.” Top pairing defencemen aren’t supposed to be sheltered the way Theodore is. Even if we grant that models are properly adjusting his competition, it’s worth asking why Vegas feels the need to shelter him so much and whether we’re willing to coronate a guy who isn’t trusted against top lines as a top defenceman in the league.

Shea Theodore Absolutely Destroys Vegas’ Ability to Finish

Remember the last few games of the Knights-Canucks series, when Vegas was completely unable to beat Thatcher Demko? That was a historic stretch of goaltending, but for Vegas fans it probably seemed like more of what they’re used to.

For the past two seasons, the Knights have had a lot of trouble finishing their scoring chances. They’ve been an elite team in terms of expected goal, shot attempt, and shot shares, but only above-average in actual goals and miserable in terms of finishing (goals scored above expected). For a team that good and with that level of talent, this is really concerning. Oftentimes when a team is scoring at a below-expected rate we expect them to “regress to the mean” and start getting bounces again, but when it happens for two seasons in a row it’s a real red flag.

Sometimes the cause of consistently below-expectation finishing is a lack of scoring talent, but the Knights have guys like Karlsson, Marchessault, Smith, Stone, and Pacioretty so that doesn’t seem right. To figure out what’s going on you have to dive deeper into their results and try to pick out causes, and Vegas has a single, glaring one:

When Shea Theodore is on the ice, the Golden Knights cannot finish their chances. Over the past two seasons, they have scored 25 fewer goals than expected with him on the ice, and the effect has been pretty sustained year-over-year. When he’s on the bench? They’re actually an above-average finishing team. In 2018-19 this was so pronounced that the Knights were legitimately a much worse team when Theodore was on the ice in terms of goals for percentage - this while he led the league in isolated scoring chance impact. Overall, the net effect that he has is almost one fewer goal per 60 minutes purely based on finishing. This is unprecedented.

What happens if you break it down and see how he impacts each of the team’s most-played guys from the past two seasons? Every one of them except Stone and Reaves had much better on-ice finishing apart from him.

So here’s the situation: Shea Theodore is the league’s best driver of scoring chances, an elite transition player, and a talented finisher in his own right. But when he’s on the ice, Vegas and its players go from being a great scoring team to absolutely unable to finish.

Solving the Mystery

To answer this question I reached out to a bunch of people: stats guys, Xs and Os experts, player development coaches, and even a former NHL player. There were a lot of ideas brainstormed, ranging from “it’s just bad luck” to complex systems-based explanations. The most convincing theories I heard made sense from two angles: expected goal models are overrating the chances (it’s on Theodore) or Vegas’ players or system are unsuited to capitalize on the chances (it’s not on Theodore).

After a lot of research (including poring over shot data and watching lots of game tape) I’ve landed on three possible explanations which I believe each contribute to this phenomenon.

Theodore generates a lot of on-ice and individual rebounds that Vegas can’t finish.

Vegas gets more forward-driven goals off the rush without Theodore than with him.

Theodore’s volume-based approach to driving offence leads to diminishing returns.

I’m going to break down each of these theories using a combination of stats and eye test-based analysis.

Rebounds

One of the guys I asked, six-year NHL veteran Patrick O’Sullivan, told me that whenever he watches the Knights he notices that they get a lot of second-chance opportunities but struggle to capitalize on them. Based on his experience, finishing chances in those split-second net-front scrambles is a skill, and he wondered whether the Knights had the players to take advantage of those high danger (and high-xG) opportunities.

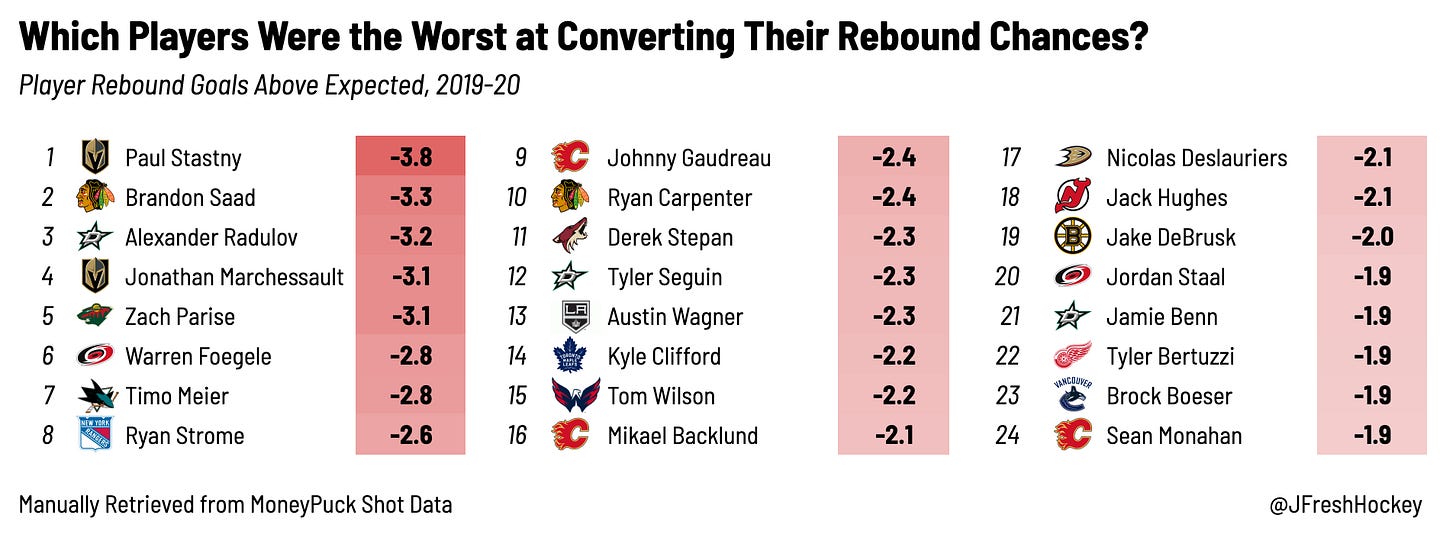

His eye test assessment was confirmed by the data. This season, Vegas finished 3rd in rebounds created and 2nd in expected goals from rebounds, but they finished 3rd last in terms of rebound goals above expected with -9. Players like Paul Stastny and Jonathan Marchessault ranked near the top of the league in rebound chances and near the bottom at actually putting them in the net.

Theodore is a big part of that gap; among defencemen he ranked 2nd in individual rebounds created, 4th in on-ice rebounds, 2nd in expected goals from on-ice rebounds, and 6th in on-ice rebound goals above expected with -4.7. In 2018-19, his rebound finishing numbers were even worse, as Vegas scored seven fewer goals than expected off of rebounds with him on the ice.

There are two possible non-exclusive explanations for this. The first is what Patrick said. Guys like Stastny and Marchessault are talented, but they’re not exactly garbagemen. Scoring goals in tight on a scramble is a lot different than sniping one off the rush, and Vegas lacks guys at the top of the roster who can be relied upon in these situations - their highest-ranked player in terms of rebound finishing was Max Pacioretty, who ranked 51st. He even noted that Vegas’ top players use relatively flat stick blades ill-suited for putting away rebounds (as opposed to the toe-curves favoured by the players who outscored expectations).

The second is that these chances - the ones that Theodore generates at a high level - are systematically overrated by expected goals models. For example, in MoneyPuck’s model, which was invaluable for this research, these types of shots were worth ~801 expected goals, but only 691 went in this season. Whether this is because of over-generous location recording or a downward trend in rebound goals, it would mean that Theodore’s on-ice expected goal numbers are inflated.

Tentative Conclusion: Theodore’s quantity-based shot generation creates plenty of rebounds which are overrated in terms of their likelihood of going in and which Vegas does not have the right players to capitalize on.

Rushes

Because prior puck movement is not yet part of public data, odd-man rushes or quick counter-attacks that lead to shots with an elevated chance of going in are not fully accounted for by expected goals models. Because these results are “baked in” to xG models, this doesn’t have a massive effect overall, but for teams or players who generate or surrender a disproportionate amount of rush chances it can have a distorting effect. I think there’s reason to believe it might for Vegas and Theodore specifically.

Each of Vegas’ top forwards this season scored over 50% of their 5v5 goals off the rush, highlighted by Karlsson, Marchessault, and Stastny scoring over two-thirds of their goals this way. Based on Theodore’s stretch pass abilities, you might expect that these happen most often with him on the ice, but actually the opposite is true. I tracked each of Vegas’ top seven forwards’ 5v5 goals over the past two seasons, noting whether they were scored on the rush, whether Theodore was on the ice, and whether Theodore was the player who carried the puck into the offensive zone. Then I used their time on ice with and without Theodore to calculate their rush goal rate with and without him.

What I found is that Vegas’ top forwards score off the rush at a higher rate when Theodore is off the ice than when he’s on it, particularly this past season. Of the dozens of rush goals I watched, not a single one of them came off a play in which Theodore (or any Vegas defenceman for that matter) carried the puck into the offensive zone. Could Theodore’s fondness for bringing the puck into the zone himself (remember those elite microstats?) actually be hurting the Knights?

Take this compilation of William Karlsson’s goals from this season. He scores seven goals on the rush, none of which feature Theodore:

Unfortunately, we don’t have access to data that could tell us whether rush chances occur at a higher rate when Theodore is off the ice. In a game I watched against the St. Louis Blues from February 13th, the team had a large number of rush shots, but they occured at a much higher rate with Theodore off the ice. I also noticed that when Theodore made stretch passes to the forwards they would typically dump the puck in and try to establish in-zone possession rather than generate off the rush. This lines up with the results; despite Theodore’s negative impact on goals, Vegas’ top forwards scored more on sustained offensive zone play with him than without him this season.

I also wonder whether the frequency with which Theodore begins his shifts in the offensive zone might be reducing the opportunity for counter-attacks.

Ultimately these questions are impossible to fully answer with public data, but there’s enough smoke here to suggest possible causation.

Tentative Conclusion: Vegas’ top forwards are primarily skilled at finishing off the rush, and Theodore doesn’t generate those types of chances in favour of a more positional attack.

Quantity-Based Scoring Chance Generation

There are multiple ways to drive scoring chances as a defenceman, and Theodore has “chosen” the way that has worked for other analytical darlings like Dougie Hamilton: taking and creating a lot of shots when he’s on the ice. The graph below shows his isolated impact on shot attempts (Corsi) for and expected goals for over the course of his career expressed as a percentile; in each of his seasons with Vegas he has been at least as much of a quantity-driver as a quality-driver.

Theodore isn’t the only example of a defenceman who generated expected goals through elite Corsi-driving whose impacts on finishing is negative. In the chart below from EvolvingWild, check out the impacts that Jeff Petry and Brent Burns had on Goals for, xGoals for, and Corsi for (the first three bars from the left respectively).

When Theodore is on the ice Vegas puts a lot of pucks on the net, including plenty of relatively harmless perimeter chances. They also score far fewer low-danger goals than expected. Those shots - because they don't go in - turn into high-xG rebounds, which then also don't go in. When watching Theodore’s unit established in the offensive zone, I noticed in a lot of cases that they lacked a sustained screen in front of the net in favour of fanning out and leaving passing options more open. This led to some great one-time chances and passing plays, but also meant that the opposing goalie could clearly see a lot of the shots from the perimeter. Considering that public data is unable to account for traffic in front of the net, there’s a chance that expected goals would overrate the value of these chances.

Tentative Conclusion: Generating scoring chances through shot quantity is not guaranteed to translate to goals, and Vegas’ system/forwards limit the extent to which both perimeter chances and rebounds are capitalized upon.

Conclusion

There can be no doubt that Shea Theodore is a fun player to watch, and with the eyes of the hockey world on him he has undoubtedly impressed in these playoffs. Is he currently riding an insane 103.6 PDO? Yes. But for the members of the analytics community who have been promoting him for the past two seasons - based on isolated metrics, heat maps, or microstats - this is been welcome validation. Theodore’s been coronated as one of the league’s truly elite defencemen, and if you needed any more proof, the legendary and famously stats-averse Jim Matheson’s blessing of an analytical darling should do the trick:

I was totally ready to join in and write a glowing breakdown about just how underrated and unparalleled he is, but I couldn’t ignore what was in front of me. The fact of the matter is that in each of the past two seasons, the Golden Knights have scored goals at a markedly higher rate with Theodore on the bench than on the ice. When Theodore is out there, Vegas controls scoring chances as measured by expected goals and Corsi, but the goals do not reflect that - not even close. The gap in finishing that turns Vegas from a top three team in the league into a mid-tier goal share squad is directly traceable to the presence of #27 on the ice. This is pretty concerning for a guy who is a.) an offensive defenceman and b.) sheltered to an unmatched extent.

Like I said before, there are two ways to interpret what I’ve found about Theodore.

Shea Theodore’s elite expected goal-driving is empty-calorie - these chances are high quality in name only and are being over-estimated by the current models. What’s the benefit of all these scoring chances if they’re not ever going to go in? The thing that makes Shea Theodore elite - his ability to drive scoring chances - is misleading, and at the end of the day what matters is creating goals, not expected goals.

It is not Shea Theodore’s fault that Vegas’ forwards can’t put a rebound in the net. Generating scoring chances as a defenceman by shooting the puck a lot is valid regardless of whether the forwards put in front of him are capable of playing that kind of game. Theodore is elite at driving shots and scoring chances, getting shots in close, carrying the puck, and setting his teammates up with crisp breakout passes. He doesn’t choose the system or personnel in front of him.

I think both takes are valid, and they could both be partly true - Theodore could simultaneously be overrated by expected goals but also let down by his Vegas teammates.

This dynamic has not taken place in the playoffs so far, as some percentage luck has finally helped Theodore out. This is a welcome change and a big part of the reason that he’s broken out. But if these anomalies keep up next season, I think we’ll have to hesitate before crowning him the next Roman Josi. On the other hand, if these playoffs represent him permanently turning the page and maybe even figuring out how to take the next step by adapting to some of those dynamics outlined above, I don’t think there will be any denying his emergence as a top offensive defenceman in the league.

I should probably add: this is an absolutely fantastic article JFresh, and commenting on it is what got me to subscribe to this newsletter. Terrific stuff, and all of your previous posts are tremendous as well. I wish hockey conversations about analytics could be as nuanced and eye-opening as what I've read here, since I used to be super-reductive against it myself ("hurr durr who cares about fancy Corsi stuff just play with some HEART and CHARACTER", not that playing with heart and character are unimportant, of course).

Theodore is not a play maker, as in making plays to free up other players on the team. He is highly skilled at bringing the puck up the ice but poor at distributing it when players are on the fly. They end up stuck at the blue line with no momentum. The more they have emphasized him bringing the puck up ice the less the seem to flow into the zone unless he takes it all the way, which happens once in 1000. Compare him to rookie defense man on vancouver. Very different style and very different use of speed and agility. My opinion, Shea needs to work on his passing while moving at full speed and distrubing the puck while others are at full speed. otherwise they just key on him and know it will be a dump in when he brings up the puck. Transition play has to be quick and crisp. The D can't take half the ice to get full speed. 3 or 4 quick strides and hit someone that is ahead of you at full spead. Once the forwards stop at the blue line momentum is gone.