Predictive Models Said the Kraken Would Be Great. They Suck. What Happened?

Breaking down Seattle's nightmarish inaugural season and why the analysts didn't see it coming.

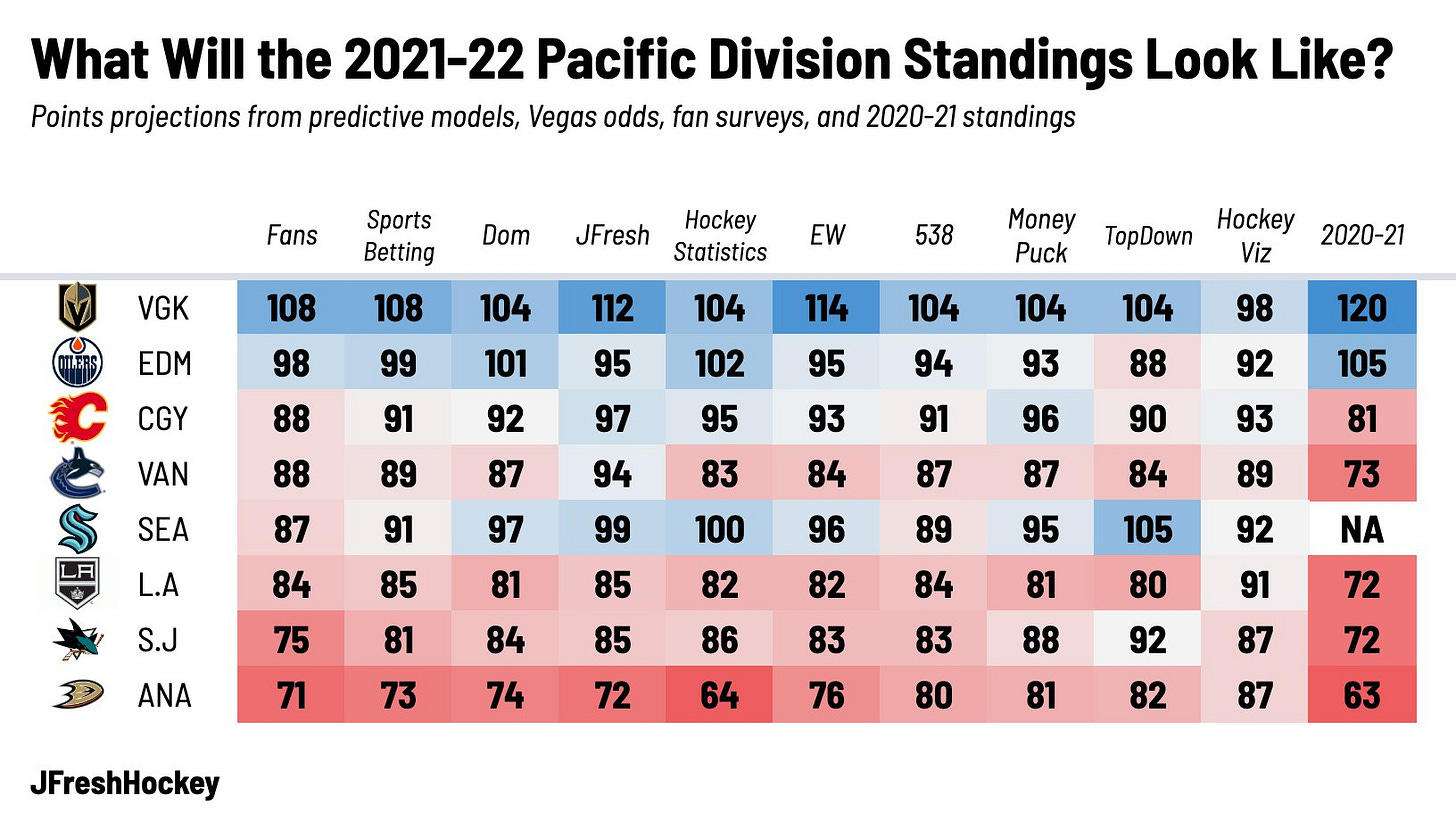

About six months ago, the Seattle Kraken selected their inaugural roster, a momentous occasion greeted by shrugs and bewilderment by people across the hockey world, traditionalists and stats nerds alike. A few days later, they dumped a pile of money on various veteran players including Philipp Grubauer, Jaden Schwartz, Alex Wennberg, Adam Larsson, and Jamie Oleksiak, prompting even more confusion about what exactly their strategy was. But regardless of the long-term advisability of going “win-now” out of the gate at such great expense, once the dust cleared the roster mostly looked… fine. Betting odds and fan consensus in surveys reflected the feeling that the Kraken had added enough decent players to be above .500 in hockey’s weakest division, landing themselves in the murky middle that teams generally prefer to avoid. But surprisingly, analytical predictive models said otherwise. Across the board, they expected the Kraken to be a solid playoff team and make the playoffs.

For example, Dom Luszczyszyn of The Athletic, whose predictive model has made both its creator and adherents significant returns by consistently beating the betting market, gave the team a 77% chance of making the playoffs and reported that an internal NHL model was similarly high on the squad. Almost every model told the same story: the Kraken would be a bad offensive team but a great defensive one, with strong enough goaltending to carry the day.

So far, the analysts, the betting markets, and most fans were wrong. The Kraken stink. They’re on pace for 60 points, 4th-worst in the NHL, and have an approximately 0% chance of making the playoffs as of this writing. On average, the fans are on track to be 28 points off their projection, while the modellers are 38 points off.

So what went wrong? How were the models and to a lesser extent fans so wrong about this team? Was it a defect in modelling, a misevaluation of players, bad luck, or external factors that couldn’t be accounted for? The two biggest culprits here are unbelievably bad goaltending and an offence that’s even worse than expected.

Goaltending

Let’s start at the most obvious aspect here. The primary reason the Kraken are as bad as they are is because they have received the worst goaltending in the NHL by far.

The Kraken have a 87.4% save percentage, 32nd in the NHL and on track to be the lowest mark recorded since the 1996 San Jose Sharks 25 seasons ago. That’s an extra goal conceded every 32 shots compared to league average or almost an extra goal per game.

To use a better stat that accounts for team defence, the Kraken have allowed 28.2 goals above expected based on the quality of chances their goalies have faced, by far the worst in the league (the Coyotes are 2nd-worst at 19.5).

That is staggeringly bad goaltending, and it has had a massive impact on the team’s performance and standings position. All things equal, if the Kraken’s goaltending was just league-average this season, they would have a goal differential of 92 goals for to 91 against, which has generally historically translated to somewhere between 88 and 94 standings points. Still not a great team and probably not in the playoffs, but a lot better than the 60 point disaster they are now. As another reference, if the Lightning had the same goaltending as the Kraken so far this season they would have a -15 goal differential and probably be on track for around 80 points.

Some people have tried to argue that this was a predictable outcome. “Philipp Grubauer was overrated because of the Avalanche’s team defence,” they say; “of course he would struggle when joining an expansion team, and the models should have seen it coming.” But this is taking something true and stretching it far past its breaking point.

It is very fair to say that Grubauer was inflated by his team’s defensive performance last season. He was nominated for the Vézina trophy due to his high save percentage and win totals, both stats that are heavily influenced by the quality of shots a team allows their goalie to face. Sure enough, goals saved above expected models, which compare a goalie’s performance to their “expected” performance based on quality of chances faced did not consider him an elite performer in 2020-21.

This was ample evidence to suggest that Grubauer would probably not be repeating as a Vézina contender this season, and it wasn’t a far stretch to subjectively speculate that he might be meh or even struggle in a new environment. It was also fair to argue that even those public models that scoffed at his Vézina nomination were too high on him, because we know that proprietary data with more detailed inputs ranked him closer to average. For example, in my model, he was projected to be the 6th-best starter in the league this season - if you asked my subjective opinion I would have had him nearer to average, which would have knocked the Kraken’s projection down solidly. Most analytically-minded observers were puzzled by Seattle’s decision to make such a costly investment in him, and applauded the Avalanche’s willingness to move on.

All of that considered, no, it was not predictable that he would be this bad.

Grubauer has not just been meh, he has not just struggled, he has not just been bad, and he hasn’t even just been the worst. He has been the worst starting goalie in hockey by a factor of two over his closest rival.

Here’s a list of the worst goalies so far this season ranked by their goals saved above expected (remember, this metric is explicitly designed to filter out team defence):

If you put all the starting goalies in the league on equal footing in terms of time on ice and compare them, Grubauer is allowing over double the extra goals compared to MacKenzie Blackwood:

I have still not found a single person, whether they’re a fan, analyst, or reporter, who predicted that he would be the worst goalie in hockey this season, let alone by this large a margin.

There are extra details to Seattle’s goaltending issues that are compelling as well: Caleb Wetherell found that 8.7% of the times the Kraken have scored, they’ve allowed a goal within the next 60 seconds, the highest rate in the league. This goes up to 14.2% if you extend the window to 120 seconds, which will not be surprising to anybody who has watched the Kraken and seen how often their momentum gets killed like this.

All of this has not prevented many from making excuses for Grubauer, placing blame on the team in front of him and acting as though his performance in Seattle is really no different than it was in Colorado - just different-quality teams in front of him. But the fact of the matter is that even if they’re not Colorado, Seattle is not a bad defensive team by any metric. In fact, they’re a quite good one. In all situations they’re the 6th-best in the league at preventing quality scoring chances (expected goals) and 8th at preventing shots on goal. According to SportLogiq, they recently ranked as the top team at the league when it comes to protecting the inner slot.

Yet when Grubauer’s struggles are brought up, it’s usually argued that he is the victim of limited public models that fail to capture how bad Seattle is defensively in front of him. Supporting this is the fact that the goals Grubauer allows are often rush chances, odd-man breaks, breakaways, slipped D coverage, etc. It’s a compelling argument, and one worth checking out. But while there is a kernel of truth to it, it is not nearly enough to offset the poor underlying play. Here are two reasons why:

Seattle has been very good at preventing the types of pre-shot plays that make chances more dangerous than models can capture. According to Corey Sznajder’s tracking they rank 3rd in preventing high-danger passes, 4th in preventing primary shot assists, 5th in preventing passes to the slot, and 5th in preventing “royal road” passes through the centre lane. As for the rush, they allow the 3rd-fewest rush opportunities in the league and 2nd-fewest chances after carrying the puck into the zone. The problem is not that they allow all these dangerous chances that Grubauer has no chance on, it’s that whenever they do, they end up in the net.

More detailed input data does not significantly change how Seattle’s goaltending is evaluated. SportLogiq has made some of its Kraken-specific data available through Alison Lukan’s postgame reports on NHL.com which allow us to compare public and private data. According to their model, which integrates goalie position, defenceman position, pre-shot movement, etc., the Kraken have allowed 25.9 goals above expected, a difference of only 2.2 from the public model. They have had a good goaltending performance in only 21% of their games so far.

So there you have it. While public projection models were at fault in terms of overrating Philipp Grubauer as a top-ten goaltender (and probably over-eager about Chris Driedger as a top backup), any model that would have settled upon this as the most probable outcome would have been broken beyond repair. Goaltending, which we know is the most random and unpredictable variable in the sport, explains the large majority of why Seattle’s results have been so much worse than expected.

An Even-Worse-Than-Expected Offence

Even in the wildest dreams of the predictive models, the Kraken were not supposed to be good offensively by any stretch of the imagination. The most common fan observation was that the team lacked offensive drivers and would struggle to score, and while some of the reasoning often used to back up those arguments didn’t fully add up (suggestions that everyone on a roster that included Jordan Eberle, Jaden Schwartz, Yanni Gourde, Mark Giordano, Jamie Oleksiak, and Adam Larsson had been “sheltered” were pretty thin), no doubt the majority of players the Kraken selected or signed were known more for their defence and forechecking than puck skills. The models also agreed that this team was going to be horrible on the powerplay, not surprising considering a dearth of elite talent.

All that said, their even strength offence creation is undoubtedly even more anemic than anticipated. Whereas they were “supposed” to be a bottom-ten offensive team, Seattle ranks dead last in expected goals for at 5v5, making them the worst in the league at creating dangerous chances.

Much of Seattle’s offence revolves around in-zone chances generated through the point. The Kraken rank 7th in the NHL in terms of the percentage of their 5v5 shots taken by defencemen and 30th in the average quality of shots taken by those defencemen, which means too many of their shots are coming right at the blueline with very little in tight. Here’s a heatmap from HockeyViz to illustrate:

Corey Sznajder’s manually tracked data adds a bit more detail to what’s going on here other than just shot location: the team doesn’t move the puck well in the zone unless it’s to get it to the point and they do not create off the rush. Only Dallas and the New York Islanders generate fewer rush chances at 5v5, while the Kraken rank 13th in chances off of in-zone attacks (like cycles or forechecks). The result is a stationary, unimaginative team firing pucks from the point, trying but evidently struggling to retrieve them since they rank 26th in rebound chances.

This leads us to something else that the models could not fully consider: coaching.

The Kraken surprised a lot of people by choosing to hire Dave Hakstol after his poor showing in Philadelphia. Some observers, like my EP Rinkside colleague Dimitri Filipovic, noted at the time that when he was the coach of the Flyers they deployed an offensive strategy that was quite out of step with the forward-thinking vision being professed by the Kraken. Here’s the Philadelphia Flyers’ offensive heatmap during his final full season with the team in 2017-18:

Look familiar? It’s all point shots with not a lot else going on. Maybe you can sneak into the playoffs with 42 wins playing like that when you have Claude Giroux and Sean Couturier, but don’t count on it happening often.

The predictive models saw a group of players coming from all different systems and philosophies and was naturally unable to predict how they would respond to Hakstol’s system - and keep in mind that it wasn’t assured that he would pursue an identical strategy to the one that got him fired four years ago. For example, Jordan Eberle, a crucial part of the Islanders’ counter-attack (and a big reason why it’s collapsed in his absence), ranks around league average in rush chances. The same is true of Jaden Schwartz, Jared McCann, Yanni Gourde, and Joonas Donskoi; the Kraken have players who have had success playing up-tempo hockey but that’s not what they have them doing.

According to Jack Han, who wrote a brief piece on the Kraken’s system today as a preview for his upcoming Hockey Tactics 2022 Playbook, Hakstol thinks very little of his players’ puck skills in transition and accordingly limits how frequently they showcase them:

SEA’s solution to its lack of elite puck carriers is to have Fs stretching to the far blue line and Ds firing long-range passes, as to spend as little time in the NZ as possible.

By shooting the puck north, SEA can catch opponents off-guard and create a rush chance. However, by not using the space underneath to create passing sequences in transition, SEA has trouble controlling the tempo and often finds itself losing rush battles against more talented teams.

As we’ve seen, the Kraken don’t lose the rush battle with their defensive play, but by hyper-accelerating their neutral zone play and then slowing things down to a crawl. The all-in long-range passes work infrequently (they rank 26th in defensive zone shot assists) and no team creates fewer chances by making passes in the neutral zone.

All the forwards’ offence has flattened, including the players who actually had a decent track record of creating chances. Here’s a comparison of how their percentile rankings in isolated even strength scoring chance impact (as measured by WAR) has changed compared to last season:

There are a couple potential explanations for this:

The players to a man aren’t as good as they were evaluated to be on their previous teams, and they’re getting exposed in Seattle.

Most of these players are veterans and at an age when these declines tend to happen.

These players were well-suited for their previous teams and not as well-suited for the system and deployment they have in Seattle.

All of these are possible and could be simultaneously true. Most fans seem to be favouring #1. I’m not as convinced in part because we’re not seeing a pattern of these players’ ex-linemates especially thriving without them - Mathew Barzal, Jason Zucker, Blake Coleman, and Brayden Schenn for example have all seen their offensive numbers diminish as well. It seems more likely to me that the team has over-reacted to its lack of top-end talent by playing an antiquated and unimaginative system and these players aren’t skilled enough to transcend it.

Conclusion

What can we learn from Seattle? You always want to be able to take away lessons from huge misses like this, even if the Kraken’s particular circumstances aren’t likely to be replicated in the near future.

The first is a reminder that goaltending is prediction poison. There was no reasonable way to anticipate that Grubauer would go from overrated but above-average starter to playing like an ECHL walk-on this season. It was always an extremely remote possibility, but in models designed to project the most probable outcome it was never going to be possible to factor it in. We know goaltending performance is unpredictable to the point of near-randomness, we know it’s the most likely variable to throw everything in the trash, and yet it’s also by far the factor that can most influence a team’s results.

The second is the importance of coaching. The way a coach chooses to implement a system and the way players fit in that system aren’t neat and tidy. There’s a reason that player models like Wins Above Replacement aim to measure player performance and not innate skill - if a player is instructed to do something that does not maximize his skillset, the results will reflect that. Adding an interpretive element when thinking about teams and systems can help, but that’s not a silver bullet either, since it adds more subjectivity and noise, and frankly we also can’t predict tidily what coaches are going to do (consider all of the fans who thought Darryl Sutter was a dinosaur who was going to turn the Flames into a dump and chase goon squad). This especially applies to special teams, where public models are the most blind and structure is the most strictly imposed.

But there’s one more nuanced one, which is the problem of looking at standings points as a monolithic number and ignoring the process and components that lead to them. It might be cathartic to see the smug stats nerds fall flat on their faces and universally get owned by this team sucking, and I won’t deny anybody the pleasure. Even if you cast aside the goaltending as pure noise, the fans were more right about this team than the models were. But plenty goes into a team’s performance apart from innate skill, things that can be considered the most “probable” outcome, and things that can be gleaned from the past performances of the players. There are things the stats can’t capture, and there are things the eye test can’t capture. The analysts trusted their models on Seattle because they had been less wrong than everybody else in the past, and they got burned. Huge misses like this are a good reminder that everyone is always wrong about predicting what will happen in this stupid, amazing sport, and all we can hope for is to be a bit less wrong.

Great stuff here, thank you. I keep going back to point #2, coaching. Everything seems to lead back to this.....giving up breakaways (which Gru can NOT stop) is usually because Hak has nothing but point shots, which, if blocked, lead to breakaways or odd-man rushes. Coaching....need to protect your goalie.

Which is even more odd to have Gru on pace for ~63 games this season, when Dreidger has been playing better as of late, odd strategy Cotton.

Then giving up a goal 14% of the time following your own goal! What in the world is this...coaching and Gru! Gru lets in 261% of expected goals in the 60 seconds following a Kraken goal!!!

What to do now: given the current spot in standings, become a seller at the deadline, stock up for next year with Beniers and a new head coach!

Thank you. Now I have nice place to point all the people who keep telling me Seattle's defense sucks and Grubauer is actually good.