In 2017, Erik Karlsson put together one of the most impressive playoff performances of the cap era, an incredible run in which he almost singlehandedly dragged the Ottawa Senators to the verge of the Stanley Cup final. Three years later, following a trade, a massive contract, and some injury issues, he has lost his status as one of the league’s top players - in TSN’s recent top 50 ranking he was left off the list entirely. According to the popular narrative, since arriving in San Jose Karlsson has been an injury-hobbled shell of his former self and an albatross on the Sharks’ payroll. As a result, a player who was the league’s marquee defenceman just over a year ago has now improbably been mostly lost in the shuffle as guys like Roman Josi and Victor Hedman dominate the position.

But has Karlsson’s decline in play since joining the Sharks actually mirrored this drop in prestige? To answer that question, I’m going to use a similar methology that I used to analyze Seth Jones, Dougie Hamilton, and Shea Theodore; diving into not only macro-level models like RAPM and Wins Above Replacement but also microstats, game tape, and scouting to sort out what’s going on and what it all means. This will involve giving a general overview of his stats, tracking stylistic changes over time, assessing whether his reputation for poor defensive play has been well-earned, and analyzing how his main defence partner in San Jose might have impacted his performance. I’ll be using stats from Evolving-Hockey, Corey Sznajder, NaturalStatTrick, and SportLogiq.

Profiling Erik Karlsson Analytically in 2020

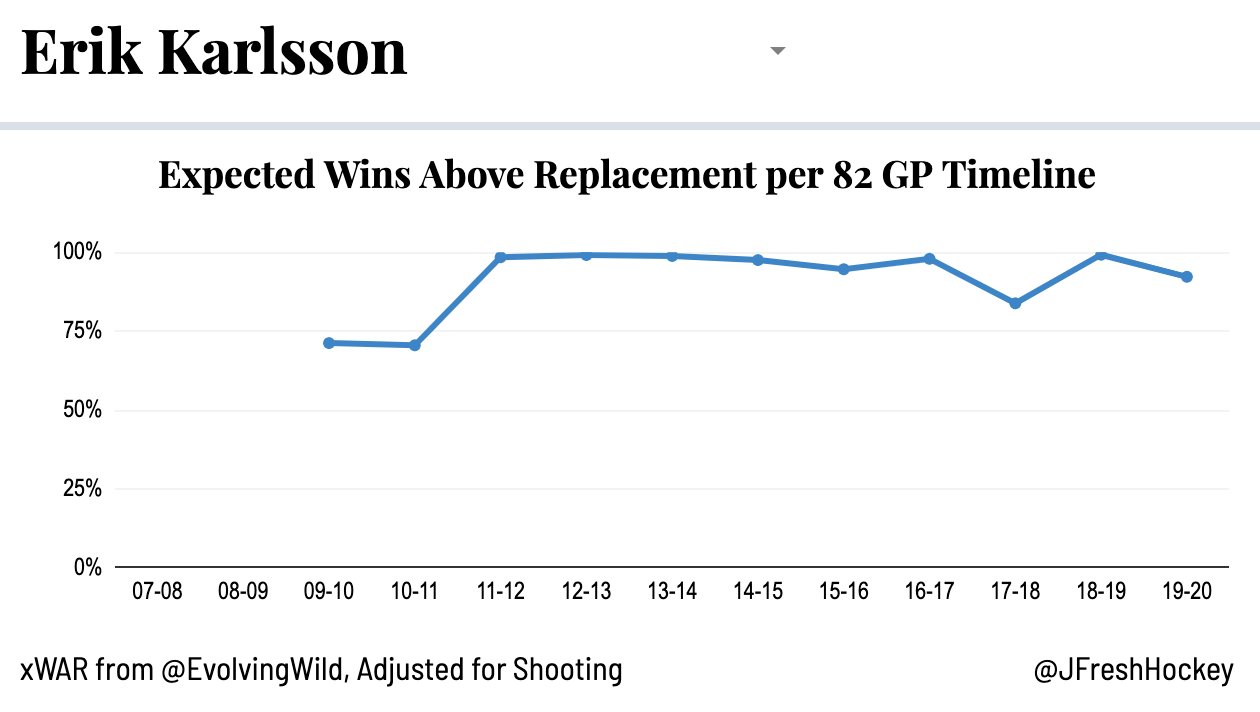

At a glance, Karlsson’s analytics are about what you would expect from him: elite offensively and mediocre-to-poor defensively in #1 minutes. He’s right there in the top tier in terms of generating scoring chances and shot attempts for, boosted by his extraordinary 2018-19 season in which he was among the league’s best blueliners. His game took a step back at both ends of the ice this season, but he still projects quite well moving forward. In terms of his career timeline, Karlsson has ranked near the top of the NHL in terms of expected Wins Above Replacement in almost every season since he broke out in 2011-12.

Based on his overall impact on the game as measured by this metric, if Karlsson is no longer in the absolute top tier of defencemen, he’s pretty damn close. But we’re going to have to go a lot deeper than this to really feel like we have a solid handle on his game.

How Karlsson’s Game Has Changed

As the timeline above shows, Karlsson has been consistently near the top of the league in terms of his overall macro-level impact on quality shot attempts. But that doesn’t mean the way he plays the game has stayed perfectly steady. In fact, some rather dramatic shifts have taken place recently that affect his contributions to his team.

The most notable one is his transition game. Anybody who’s watched Karlsson play will tell you that a huge part of his effectiveness is his ability to move the puck out of the offensive one and lead the breakout with the puck on his stick. In 2017-18, Karlsson’s 3.3 stretch passes per game ranked first in the NHL; in 2018-19, he was the league’s most effective possession exit driver. But something changed this season.

There are three big shifts visible here:

Karlsson entered the offensive zone with the puck a lot more

Karlsson exited the defensive zone with the puck a lot less

Karlsson’s transition game is much less possession-based and includes a lot more dump-outs and dump-ins.

Possession entries is kind of a tough stat to evaluate for defencemen. It’s often viewed as a positive thing, but the actual value of having a blueliner lead the rush is uncertain at best and dubious at worst. It’s risky from a defensive standpoint, and can disrupt the flow of offence as well. Based on SportLogiq data made available to OilersNation, Karlsson’s 58 5v5 entries ranked 39th in the league. Of those entries, 35% led to a shot attempt and 22% led to a scoring chance - not awful compared to his peers, but not standout either. Karlsson shifting away from moving the puck to his forwards in favour of doing it all himself might signal a distrust in the players in front of him to get the job done, but it’s not evident that taking matters into his own hands has paid off in any meaningful way.

In 2019-20, Karlsson was shockingly average in terms of leaving his zone without dumping the puck out - a very abrupt change considering the breakout was a huge part of what made him elite in the past. As the Sharks’ foremost transition player, this had a huge impact on the team’s overall ability to move the puck out of the defensive zone, and the team finished dead last in the NHL in terms of possession exit percentage, dumping pucks out or failing to exit the zone 65% of the time. Why the sudden change? It could be factors out of his control, such as a change in system or a difference in his forwards’ ability to get open for breakout passes. Brent Burns also saw a decline in possession exit percentage this season. But there could also be a technical explanation.

Anyone who's watched my beer league games knows I'm personally in as good a position to critique Erik Karlsson's skating as I am to correct his Swedish grammar. With that in mind, I'll defer to skills consultant and former Marlies assistant coach Jack Han, who recently published a tape breakdown of Karlsson’s regression as a skater from 2012 to 2016 to 2020. In it, he concludes that a procession of lower body injuries has robbed Karlsson of much of his agility and explosiveness, which has had major consequences for his defensive play. While his straight line speed is still there (which helps with zone entries), he’s winning races to DZ pucks by far tighter margins than he used to, forcing him to dump the puck out a lot more often. A major difference between prime and 2020 Karlsson is that the latter is far more prone to just whacking pucks out of the zone rather than skating or breaking them out. Without a partner who can move the puck, opposing forwards can be confident mobbing Karlsson and taking away his time and space. But more on that later.

Was Erik Karlsson Ever Bad Defensively?

Erik Karlsson’s impact on the defensive side of the puck has always been a source of contention. During his prime with the Senators, Karlsson was considered by many hockey fans to be an absolute liability defensively. But this was far from unanimous. Those in the then-fledgling analytical community countered this claim by making the case that his ability to control puck possession meant that his offensive play translated indirectly into effective defence. Backing up this argument were his strong Corsi (shot attempt) against numbers, which appeared to show that overall he was giving up very little.

But with more tools and models available to us now, we can scrutinize this notion in retrospect. RAPM stats, developed by EvolvingWild, estimate a player’s isolated impact on various on-ice metrics, adjusting for things like teammates, competition, zone starts, etc. These numbers are a lot sharper than the raw or relative ones we relied upon in the past. Applying that model to previous seasons gives us a much more complete story:

Based on the far-right column, it is clearly true that Karlsson’s ability to control possession limits the number of shot attempts his goalie faces - he was above-average as a shot suppressor in seven of nine seasons, and 2019-20 was his best yet in that regard. But when you incorporate the quality of those shots, things change quite a bit. Especially with the Senators, Karlsson didn’t give up much quantity, but that was more than cancelled out by the quality of chances he gave up. Karlsson’s poor on-ice goals against numbers were typically blamed on Craig Anderson, but a look at the expected goals against suggests that the blueliner had more to do with it than first appeared - not to mention that in terms of career RAPM goals against, only Jack Johnson ranks worse than him.

Essentially, in retrospect it appears that the eye test crowd were onto something that Corsi didn’t catch. Karlsson was controlling possession, but the chances he did allow were really really good, and ended up in the back of the net quite frequently. But how could a defenceman give up so much quality and so little quantity?

We have some stats that solidify the case for Karlsson as a decent in-zone defender. Proprietary stats collected by SportLogiq (and occasionally published by The Point Hockey and Andrew Berkshire of Sportsnet) have long suggested that Karlsson is a high-event defensive player in a good way. In his final season with Ottawa, he ranked very well in stick checks, blocked passes, and even defensive zone turnover rate. These actions probably contributed (and still contribute) in a large way to his solid shot suppression against the cycle.

Things get trickier when we turn our attention to the rush. Karlsson has always played a very aggressive style all over the ice. He’s willing to take risks, knowing he has the skill to make them pay off in the aggregate. For example, on the play below he decides to cycle into the slot in the offensive zone, and this miscalculation leads to a two-on-one which Marc-Édouard Vlasic fortunately is able to negate:

These types of chances aren’t worth much in terms of Corsi, but they look a lot more dangerous in expected goals and even worse in actual goals (since odd-man rush and passing data don’t exist in public data).

Karlsson is similarly aggressive when defending his blueline. He has always ranked very well in terms of denying zone entries, and the past two seasons have been no different (91st and 95th percentile in ‘19 and ‘20 respectively). His aptitude at this has also been used as evidence of his underrated defensive play. However, this type of play at the blueline is risk-reward. On one hand, it forces the puck carrier to make a play quickly and can force turnovers or uncontrolled entries. That’s good, and is probably a big reason why his shot attempt differentials are so strong. Here are two examples against the Blues from this season:

On the other, if the defender gets beat on a play like this, it often leads to an odd-man rush or partial break. That’s why many of the league’s best defensive defenceman elect to play a more conservative gap and focus on closing off the middle of the ice, and many coaches prefer a similar reserve.

Here’s where we get into some murky territory. Strictly speaking, the scripture in hockey analytics is that defencemen are not responsible for the goaltending behind them - we analyze them using shots and scoring chances alone. But we also know that expected goal models aren’t perfect, and there are certain types of shots that are underweighted due to the limitations of public data, such as cross-seam one-timers, breakaways, and odd-man-rushes. There’s reason to believe that they’re the types of shots Karlsson forces his goalies to face thanks to his aggressive play without the puck: he consistently ranks very poorly among his teammates when it comes to on-ice goals saved above expected, with the outlier exception of this season.

Notice the major dip after the 2014-15 season, which is reflective of the gap between RAPM GA and xGA from before. What this suggests (inconclusively) is that while Karlsson has always allowed a lot more quality against than quantity, in the past six seasons he has allowed so much quality that current expected goal models can’t even capture it. Without access to mountains of manually tracked private stats, it’s impossible to know exactly the extent to which Karlsson’s play creates odd-man rushes against compared to his teammates. But there’s a lot of smoke there, and it fits in nicely with some of the broader narratives around him. Han points out in his breakdown that even by 2016 he notices mechanical issues in Karlsson’s defensive zone skating, specifically that he is “eminently exploitable when forced to pivot.” So we’ve got a player who is extremely aggressive who can often be beat due to injuries affecting his agility - seems very plausible that he would give up high quality chances, including many odd-man rushes.

If this is indeed the case, as Karlsson’s skating deteriorates further it’s one he’ll have to adjust to quickly - especially if he doesn’t have a partner he can rely upon to clean up the mess. Speaking of which…

Karlsson’s Vlasic Pickle

One of Karlsson’s biggest issues moving forward is his partner, Marc-Édouard Vlasic. For almost a decade, Vlasic was one of the league’s best defensive defenceman, an absolute stud when it came to preventing scoring chances against who negated opponents on a nightly basis. Defying the myth that cerebral defensive players always age well, Vlasic’s effectiveness has nose-dived following injuries that reduced his footspeed.

As Vlasic’s gap control and ability to win races to loose pucks have eroded, his reputation as the perfect defensive counterpart to a roving offensive defenceman has become less and less appropriate. Erik Karlsson has discovered this first-hand:

With or Without You stats are extremely flawed, and shouldn’t by any means be taken as gospel. The extent to which Karlsson’s results at both ends of the ice have been affected by Vlasic is curious though. The two allow more and better scoring chances against when paired up, which is not a very good sign. It would be intruiging if the huge gap in goals against was because of Vlasic bailing Karlsson out on odd-man rushes (like the one shown above), but since it’s only the case in one season it is very premature to assume that it’s anything but luck.

The two spent the majority of 2019-20 together, and his only other partner during his time in San Jose has been the now-departed Brenden Dillon. The Sharks have not acquired a top-four defenceman this offseason, meaning that it is almost a sure thing that Vlasic - Karlsson will once more be the team’s top pairing (Radim Simek, their second left defenceman, has played almost exclusively with Brent Burns in his career). If Vlasic continues to struggle and Karlsson refuses to adapt his game accordingly, things could get ugly as the two decline even more.

Conclusion

There is justifiable reason to be pessimistic about Erik Karlsson moving forward. The concerns about his skating and particularly agility are well-founded and reflected in the stats as well as the eye test. There is little indication that he has adapted his game in such a way that mitigates these issues, and in fact he’s playing even more aggressively than ever. With a declining roster in front of him and a washed up stay-at-home defenceman on his left side, the returns could keep on diminishing. As smart a player as Karlsson is, there’s no doubt that his physical talents were a major part of what made him a generational offensive defenceman, and aging gracefully will be a challenge; the worst case scenario for him is that his trajectory mirrors P.K. Subban, whose performance has plummeted due to similar injury-related skating issues.

But with all the negativity surrounding Karlsson - the ugly contract, the floundering franchise, that weird moustache - it’s easy to lose sight of the calibre of player that he still is. 2020 Erik Karlsson is still one of the league’s best offensive defencemen, a possession monster with dynamic playmaking ability whose first season in San Jose was among his best ever and whose “disappointing” performances are better than the vast majority of players in the league will ever reach. He might not be in the absolute top tier of blueliners anymore, but as of this moment he is still an excellent #1 defenceman. And who knows - maybe ten months off will give him the rest he needs to properly rehabilitate those injuries and reset his career. We should all hope that this is the case, because the sport is better when Erik Karlsson is at the top of his game.

As a Sens fan, i totally with the analysis. I was very happy to have him from an offensive stand point, but he was frustrating to watch on most defensive plays. And since it's defense that wins championships, I was firmly on the trade-him train (since about 2015). I never thought we could win him, especially if he was in a leadership role.

The analytics dont matter if he can't stay healthy and on the ice. Since he's joined the sharks, he's played about 50 games a season, and has only played a full season 3x out of 9. Hes there to score goals, and run the point. He will succeed when his defense can be absorbed by a true defense first star (vlassic a couple years ago). Right now, hes a guy that costs a lot towards the cap, and lost draft picks.